Unlocking High-Integrity Restoration at Scale: Early Insights from Symbiosis Coalition’s First RFP

The Symbiosis Coalition, the advance market commitment for nature-based carbon removal, launched last year with a goal to contract up to 20 million tonnes of high-quality, nature-based carbon removal credits by 2030, and supercharge a new wave of restoration.

We launched our first Request for Proposals (RFP) for reforestation and agroforestry projects at the end of last year to translate that ambition into action. We’re excited to share lessons learned along the way, both highlights and hurdles, to empower more buyers, developers, and investors to act. These are insights from the first phase of our RFP process, and we look forward to sharing more as the RFP progresses.

How the RFP Worked

Our first RFP was open to reforestation and agroforestry projects worldwide. Projects had to meet our Quality Criteria, be ready to sign long-term offtake agreements, and demonstrate potential for scale – ideally at least 500,000 tonnes of carbon removal by 2035, and at least 1 million tonnes over their lifetime. We also encouraged projects with strong local leadership and meaningful ecological, biodiversity, or social benefits to apply.

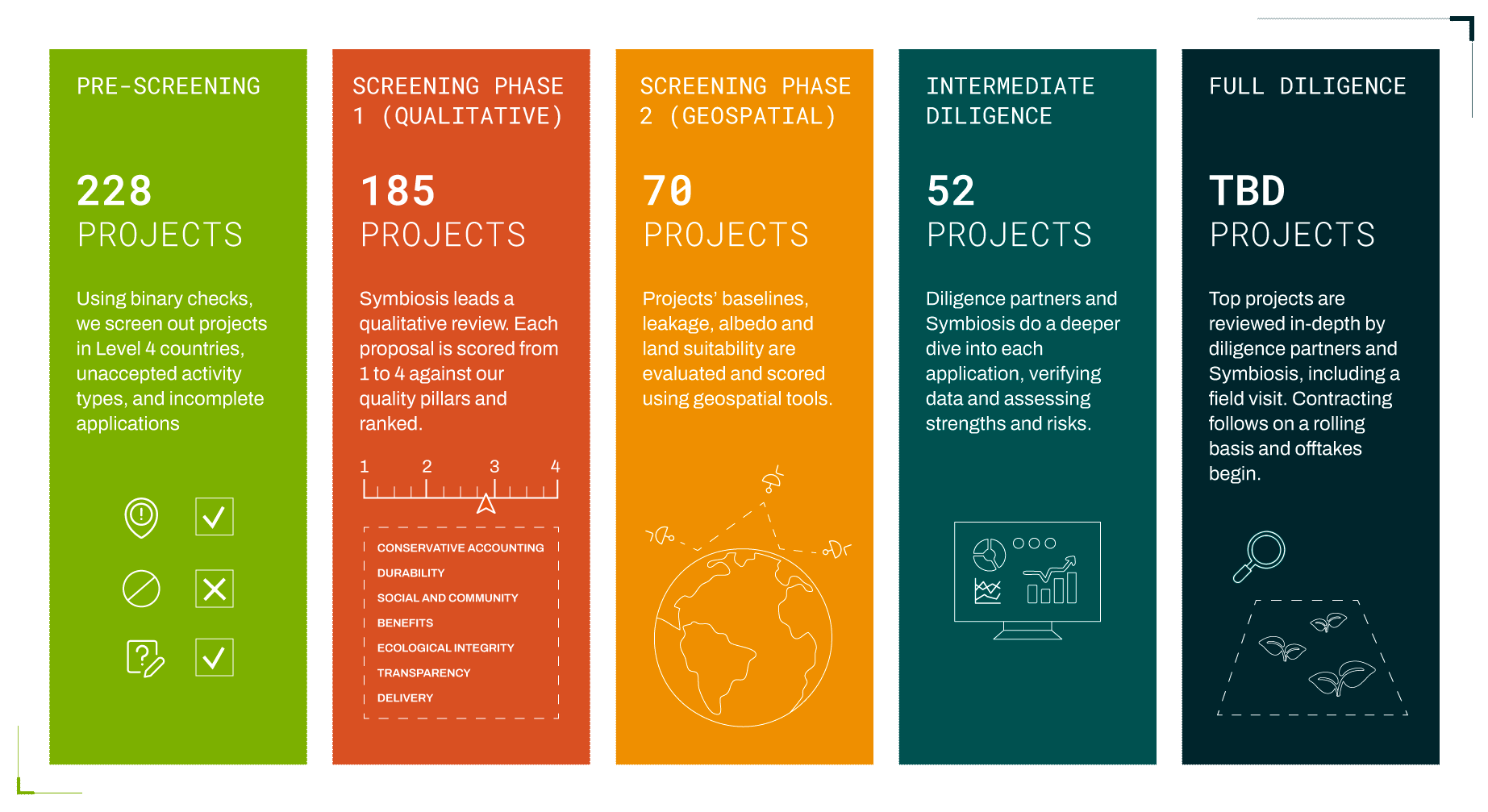

Overview of the Symbiosis RFP review process, with the number of proposals that proceeded to each stage. More detail on our RFP process (including frequently asked questions, guidelines, and estimated timeline) can be found here.

Key Takeaways

Although it’s too early to say which projects ultimately meet our Quality Criteria and will successfully sign offtake agreements with Symbiosis members, here are some initial insights from the first stage of the RFP.

1. Reforestation and agroforestry carbon removal projects are nascent, with promising, large-scale potential for impact.

The RFP response exceeded our expectations: we reviewed 185 proposals in total (of the 228 submissions, 19% were rejected in pre-screening due to being incomplete, unsuitable project types, too small, or in U.S. State Department Level 4 countries). The 185 proposals came from 153 different project developer organizations, representing 49 countries across six continents. Brazil (18%), India (12%), the United States (4%), Colombia (4%), and Ghana (4%) made up the highest proportion of projects, with a long tail of projects in other countries, representing the geographical breadth of nature-based carbon removal.

Profile of All Screened Projects

Highlights aggregated from all 185 10-year offtake proposals reviewed.

On the Restoration Activities graph: project developers self-identified project activities (for example, sometimes labeling their projects as “afforestation” even though it did not correspond with the Symbiosis adopted definition, which defines afforestation as the artificial establishment of forests or tree plantations on lands which previously did not support natural forest ecosystems - defined as woody vegetation with a height of at least 5 meters and a canopy density of at least 20-25% at 30 meters existing until 50 years ago) and could submit multiple activity types per project.

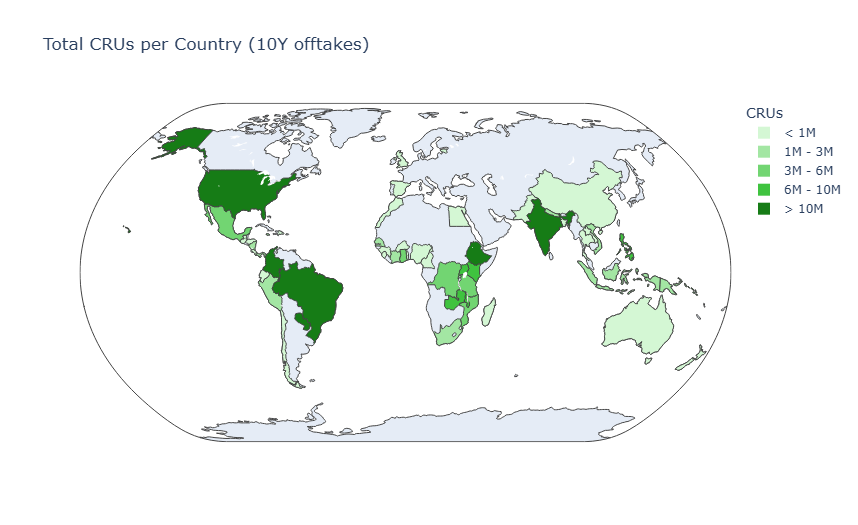

Total Volume (in CRUs) per Country

Locations of 185 projects reviewed, colored by total CRUs (carbon removal units) proposed for 10-year offtakes.

We asked each project to present a 10-year offtake proposal, with the option to propose 15, 20, and 30-year offtakes as well. Together, the 10-year offtake proposals from the 185 projects reviewed covered over 6.6 million hectares - an area larger than Costa Rica - with a reported expansion potential of nearly 12 million ha planted by 2030. Combined, the projects proposed to remove over 180 million tonnes of CO2e over the course of 10 years. At their full expansion potential, these projects could collectively deliver over 2.3 billion tonnes of CO2e removed by 2055.

In our initial evaluations of these proposals, a primary consideration was whether the interventions were ecologically appropriate for the biomes and ecoregions in which they were located (as defined by Olson et al, 2001). About half of the proposed CRUs and hectares were situated in biomes generally suitable for forest restoration, such as tropical or temperate forests. The remainder were in biomes appropriate for certain interventions, for example, in woodlands like the Miombo, which would be suitable for woodland restoration rather than high-density reforestation, or in savanna or shrubland ecosystems suitable only for certain agroforestry interventions. For projects in these latter biomes, we looked to ensure that the proposed interventions were appropriate for the social and ecological context.

The majority of projects reviewed are still in their early stages, with 78% having a feasibility study or draft PDD, and only 5% already issuing credits. The scale-up potential of restoration is tremendous - if the demand is there to meet it.

After screening, our next step was to vet projects more deeply against our Quality Criteria in intermediate diligence, both to see which ones already meet the Criteria and to identify others that could get there with additional technical guidance and support. Because we received so many more proposals than expected, many of which appear to have the potential to meet our Quality Criteria, we took steps to bring more projects through to the next stages than we had originally planned.

2. Projects generally demonstrated strong ecological and social benefits, with addressable issues around conservative carbon accounting and durability.

Symbiosis is dedicated to catalyzing nature-based carbon removal projects that provide certainty of climate impact and advance positive outcomes for nature and people, but struggle to access low-cost financing today. In this RFP, we sought reforestation and agroforestry projects that met our Quality Criteria but were also mature enough to undergo a rigorous diligence process and sign a long-term offtake agreement with our members this year. Our developer readiness checklist laid out the documents and data we looked for to assess the quality and maturity of projects, regardless of the methodology used.

We reviewed the unique environmental, social, commercial, and geopolitical context of each project and scored submissions based on their alignment to our Quality Pillars and Reforestation and Agroforestry Quality Criteria. In the screening phases, we identified common strengths and areas for improvement, as well as instances where carbon finance isn’t the right fit (e.g., commercial-scale forestry projects that are already viable without carbon finance).

On strengths:

Projects consistently demonstrated strong commitments to ecological impact and stakeholder engagement and consultation. Across both phases of screening (see infographic above), projects scored highest on average against the Ecological Integrity Quality Pillar, signaling promising potential for positive ecological impact. We assessed potential positive ecological impact based on Species Threat Abatement and Restoration datasets from the Integrated Biodiversity Assessment Tool. Projects that reached intermediate diligence stood out for demonstrating strong structural elements, including comprehensive and robust stakeholder engagement and benefit sharing plans, and meaningful experience in their local regions, either through in-house expertise or partnerships with local organizations.

We’re encouraged to see this next generation of projects place such a clear emphasis on managing risks related to, and pursuing positive impact for, biodiversity and local and indigenous communities.

On areas for improvement:

Weaker RFP submissions generally exhibited two main types of addressable weaknesses, technical and structural, most often related to our Conservative Carbon Accounting and Durability Quality Pillars.

First, many early-stage projects needed to refine their technical approach before they could proceed to intermediate diligence. For example, we noted uncertainties in carbon projection and baseline calculations – often due to reliance on equations or data that aren’t sufficiently representative of the local ecological context (i.e., climate and soil conditions). In some cases, data does not exist today to justify the carbon calculations we saw, highlighting opportunities to support data collection and research, such as the development of new allometric equations, to strengthen the carbon calculations of those projects and future projects working in similar geographies or eco-regions. In the case of durability, many projects did not articulate a clear theory of change for how the project would support a sustainable forest transition that would last beyond the timeline of the carbon project. In some cases, these issues can be resolved, but projects need technical guidance and time to address them.

Second, we saw structural issues that would require significant changes to project design or business models before aligning with our Quality Criteria. For example, questions arose around additionality in working forests when projects with a mix of exotic or high-value commercial timber species in production areas and native species in restoration areas were located in geographies with developed timber market infrastructure and could not demonstrate the necessity of carbon finance for the establishment of the production areas. Another example is concerns around incomplete stakeholder mapping and engagement plans. These concerns arose with projects operating in areas with complex land tenure and local resource use norms and institutions, and where not all groups had been properly identified and/or included, threatening the delivery and durability of the project. In both of these examples, proposals would be considered as incompatible with our Quality Criteria at this time, but with the potential to address these issues over the coming months.

Both categories of weaknesses are addressable, and we aim to share lessons learned and guidance in the future that could help projects fix those issues. In the meantime, we encourage these projects to check out our early project support database.

Where carbon finance isn’t the right fit:

In some instances, projects were fundamentally unsuited to carbon finance as defined by our Quality Criteria, and no project design changes would justify a future carbon project. This category of projects included those proposed in areas not ecologically suitable for reforestation, where the albedo effect would negate the benefits of carbon removal, or where the leakage or lack of additionality associated with the project made carbon finance fundamentally unfeasible. We used geospatial land suitability, leakage risk, and baselining evaluation tools along with datasets generated by Hasler et al, 2024 to help assess this foundational mismatch between proposed activities and carbon finance. Given the many benefits of nature (e.g., biodiversity conservation, soil erosion control), these projects could still be valuable to pursue, but not with climate impact as the main goal.

Symbiosis used geospatial data to assess key factors impacting suitability for a reforestation project. The selected project boundary is illustrative only.

Source: Pachama's Land Suitability Tool

3. Offtake is needed but not sufficient. Other forms of financing and technical assistance are necessary to unlock the scale of impact the world needs.

Symbiosis aims to unlock lower-cost financing for high-integrity nature-based carbon removal through bankable offtake agreements that help to derisk projects in the eyes of investors. Many project submissions seemed to validate Symbiosis’ hypothesis that offtakes with creditworthy buyers are a critical unlock for project financing. Letters of intent from investors contingent on reaching an offtake agreement with Symbiosis members helped us understand where a Symbiosis offtake could be catalytic, as well as a project’s implementation readiness. We encourage earlier-stage projects to engage with investors such as those in our investor database sooner rather than later in order to improve their chances of securing an offtake and demonstrating readiness to implement.

Many projects need more than just offtake agreements - they need technical guidance, research, and earlier stage investment to reach enough maturity to enter into a long-term offtake agreement. There is a large swath of projects that could be aligned with the Symbiosis Quality Criteria, but just need more support and time to get there.

What’s Next

We’ve been in the intermediate diligence phase with the first subset of Symbiosis RFP applicants. We will soon move to full diligence for an even smaller number of projects. In full diligence, we take a deeper look at alignment with our Quality Criteria, combining desk research with on-the-ground field visits to understand risks associated with the project and potential ways to mitigate those, as well as assess a project’s ability to deliver on its intended impact.

Our early RFP results reinforce the science that nature-based solutions can provide near-term climate change mitigation and carbon removal at scale - and that efforts like Symbiosis Coalition have a big role to play in helping the world untap this potential. Realizing this next generation of projects will require not just catalytic offtake agreements, but also technical support, research, and partnership to ensure these early-stage projects can achieve the quality and scale needed for real impact.

Demand is key to unlocking the potential of this next generation of restoration projects. Symbiosis continues to welcome conversations with prospective corporate buyers who are committed to ambitious, science-based decarbonization and sourcing high-quality, nature-based carbon removals. Inquiries can be directed to buyers@symbiosiscoalition.org. We encourage mission-aligned developers, investors, and other stakeholders to sign up for future RFP updates and Symbiosis news by following us on LinkedIn.

Special thank you to Yale School of the Environment intern Olivia Rhodes for her data analysis and contributions!